The Legacy of a Genius: Timeless Reflections, Ideas, and Insights

Leonardo da Vinci was an exceptional human. A master in various fields

Leonardo da Vinci was an exceptional human. The epitome of the iconic Renaissance man, he was a master in various fields, including painting, sculpture, architecture, engineering, mathematics, music, and literature.

What set Leonardo apart from other men?

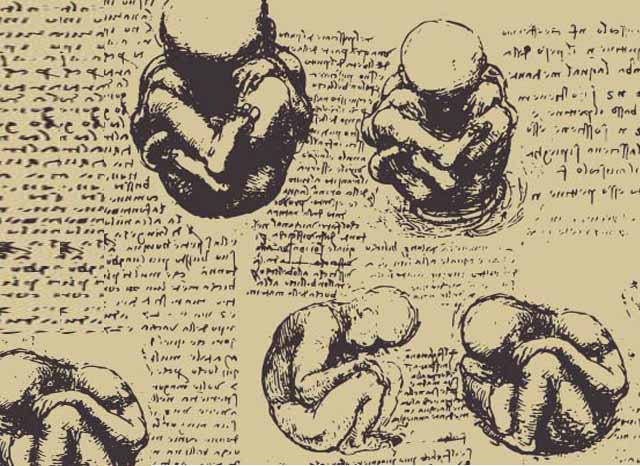

Leonardo had an extraordinary ability to combine artistic and scientific knowledge to create beautiful and proportionally accurate works of art. What sets Leonardo apart from other men, then and now, is his insatiable curiosity and his keen observational skills. He deeply desired to learn and understand as much as possible about the physical world. He constantly pushed himself to explore new ideas and improve his skills in various fields. To this end, Leonardo meticulously recorded his observations in notebooks, also known as codexes using drawings, written notes, and mathematical equations.

We should all be as curious as Leonardo. We could all take a page from one of Leo’s notebooks and follow his advice! Here is a brief history of Leonardo da Vinci and some of his wisdom.

How a Watermill Inspired Leonardo Da Vinci’s Brilliant Mind

Leonardo Da Vinci was born on April 15, 1452, in the small village of Vinci, far from the big cities. The place he was born in was no bigger than a chicken coop. As a child, his passion for machines and gadgets began because he was fascinated by the village mill. A small house was constructed over a fast-moving stream containing a marvelous machine. As the water flowed by, it caused the wooden paddles of a turbine to turn, channeling kinetic energy to grind grain into flour. And just as a watermill continuously turned by the constant flow of water, Leonardo’s fluid mind was set in motion, and he began constantly seeking out new knowledge and experiences.

Leonardo’s uncle, Francesco, gave him a pen and told him to draw. And away he went! Leonardo began to draw everything he saw, from the Arno valley’s landscape to people’s faces — the ugly and the beautiful.

Leonardo’s Vision of Beauty: A Reflection of Universal Harmon

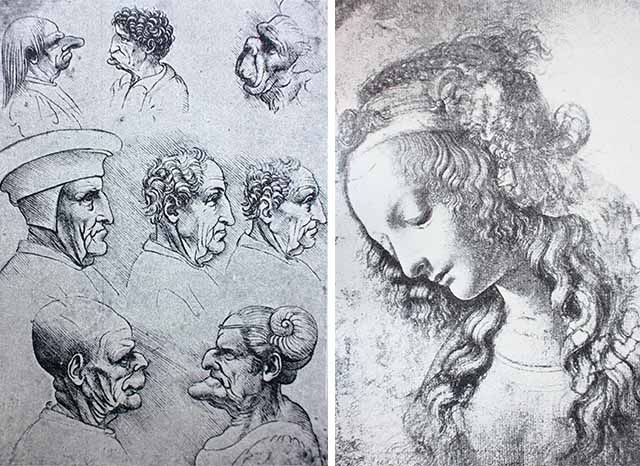

Leonardo da Vinci believed beauty was essential to art, nature, and the human experience. He saw beauty as a reflection of the natural order and harmony of the universe. He believed it could elevate the human spirit and inspire joy and wonder. At the same time, Leonardo also recognized a dark side to life. That ugliness, decay, and imperfection were inevitable aspects of the natural world. Beauty was more beautiful when contrasted with the ugly, and malformations were more horrific when compared to something divinely proportional. He believed that it was the artist’s role to capture and represent these aspects of reality and to use them to create a sense of balance and contrast in their works of art.

How Verrocchio Shaped Leonardo’s Artistic Path

His father was impressed by his son’s artistic abilities and decided Leonardo should study in Florence under the artist Andrea del Verrocchio. The Florentine Master played a significant role in shaping Leonardo’s early artistic development. He even allowed Leonardo to paint a pair of angels in one of his most famous works, “Baptism of Christ.” It is said when Verrocchio saw Leonardo’s angel, the master artist was so impressed by his apprentice’s skill and creativity he decided to give up painting altogether.

He [Verrochio] was humbled and, believing he could never match his student’s talent, declared he had nothing more to teach him. This may be apocryphal, but the two artists had a close influential relationship

The Lady and the Ermine: Leonardo’s Genius in Symbolism and Detai

Leonardo’s talents quickly became known in Florence and Milan, attracting the attention of wealthy patrons and fellow artists. As his reputation grew, he was contracted to paint numerous portraits, including the one above of Cecilia Gallerani, a Milanese noblewoman and mistress of Ludovico Sforza. The ermine she holds in her lap is directly related to the lady’s surname, which in greek is “galê.” An ermine was also frequently used as Ludovico’s emblem. In medieval bestiaries, an ermine represented the virtues of balance and restraint. Leonardo cleverly combined these elements and captured the tilt of the head and the slant of the eyes of the animal and the woman similarly. As demonstrated by this painting, Leonardo’s fertile mind constantly sought out clever connections… and you can most certainly bet he spent time studying the skull of the animal and its soft silky fur before painting this portrait.

Leonardo’s Quest for Knowledge: The Anatomy of Art

You can’t execute a masterful painting of the human body without having studied it. Thus Leonardo studied the anatomy of dead bodies of animals, young, old, and women. He also drew the internal organs until it was forbidden to continue. Although they may have contributed to medical progress, Leonardo’s drawings were forgotten for nearly 400 years.

Imagining the Impossible: Leonardo’s World of Fantastic Creatures

Leonardo always had surprising ideas. He used his wits to create fantastic images like unicorns or mysterious creatures like elephants that played musical instruments, sea monsters, Neptune the sea king, dragons, and monstrous heads. He drew large and impressive war horses, but even the little felines he made were not for the discount and had the power to be a masterpiece.

Leonardo’s Dream of Flight: A Vision of Freedom and Exploration

Leonardo dreamed of flying, and maybe the idea of having total freedom struck him and fueled his desire to invent flying gadgets so that he could visit far-off lands and see mysterious creatures and people. Legend has it that he wandered the streets of Florence with a lizard on his shoulders. Once at the market, when Leonardo saw birds in cages, he bought all of them and immediately set them free and watched in satisfaction as they flew away. He said, “If only I were one of them.”

The Art of Sfumato: Leonardo’s Revolutionary Painting Technique

The revolutionary artist experimented with new oil painting methods called “Sfumato.” It is a technique in which the artist blends layers of oil paint to create a foggy, dreamlike effect. Leonardo created a realistic sense of depth and volume by combining soft “smoky” brush strokes with light and dark colors (chiaroscuro). Look closely at the background of the Mona Lisa, and you will see this technique. Leonardo also used this soft smokey way of painting to slightly blur the corners of La Giocanda’s mouth so that the smile simultaneously seems present and absent. This creates a sense of mystery and intrigue and has become one of the most iconic aspects of Leonardo’s painting.

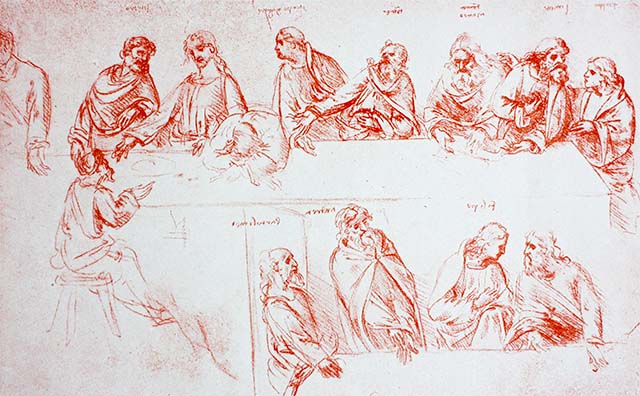

The artist saw art as an ongoing process of exploration and discovery. He once said, “Art is never finished, just abandoned.” Because he was obsessed with perfection, Leonardo often left his paintings unfinished. Il Cenacolo, or “The Last Super” is one of his most famous unfinished works; while working on this fresco, Leonardo became so absorbed in the painting that he sometimes forgot to eat or sleep. He spent hours studying the faces of his subjects, trying to capture their emotions and expressions in detail.

Here is more of Leonardo’s wisdom

Cerca le divine proporzioni che sono in tutte le naturali cose.

Seek the divine proportions that are in all natural things.

Un pittore è padrone di tutte le cose che poteva immaginare.

A painter is the master of all things he can imagine.

Non chi comincia, ma quel che persevera. Solo chi persevera ottiene risultati, nell’istruzione e nell’arte. Anche se Leonardo non ha terminato molte delle sue opere, l’essere di Leo non ha mai smesso di persevera.

It is not who begins but who perseveres. Only those who strive will obtain results in education and art. And although Leonardo did not finish many of his works, the true essence of Leonardo was to continue experimenting and evolving.

La solitudine non manca vantaggi. Chi è solo, è tutto suo.

Keeping your own company does not lack advantages.

He who is alone has everything to himself.

Non nascondere i tuoi lavori. Metti in

mostra per condividere le tue idee.

Don’t hide your work. Showcase what you have

created and share your ideas with others.

Sii innovativo e vai controcorrente. Invece di seguire gli altri, vai nella direzione opposta. Anche un pesce morto segue la corrente. Ci vuole un pesce vivo e attivo per nuotare controcorrente.

Be innovative. Instead of following others, go in the opposite direction. Even a dead fish follows the current. It takes a live and active fish to swim against the tide.

Ascolta pazientemente le critiche. Considera sempre se coloro che ti criticano hanno ragione o meno. In tal caso, correggi questi errori. In caso contrario, comportati come se non capissi cosa hanno detto.

Listen to criticism patiently. Always consider whether or not those who find fault with you are right. If so, correct these faults. If not, act as if you did not understand what they said.

Sii originale. Non imitare gli altri;

ma solo la natura.

Don’t hide your work. Showcase what you

have created and share your ideas with others.

Domanda sempre. Le domande sono

più importanti delle risposte.

Question always. Questions are

more important than answers.

Imparare non è un obblio. È una necessità. Si impara facendo cose, si impara risolvendo problemi.

Learning is not an obligation. It is a necessity.

You learn by doing things; you learn by solving problems.

Tieni il cervello attivo. Come il ferro arrugginisce dalla mancanza di uso, come l’acqua va male se stagnante o con il freddo diventa ghiaccio, così l’ingegno senza esercizio si guasta.

Keep your brain active. As iron rusts from lack of use, as water goes bad if stagnant or with the cold becomes ice, ingenuity stalls out and becomes stale without exercise.

Cerca la semplicità. La semplicità è

il massimo della sofisticazione.

Keep things simple. Simplicity

is the ultimate in sophistication.

Correggi l’amico in segreto

e lodalo davanti agli altri.

Cerca gioia e amore nella vita. L’amore è il rifiuto

dell’odio e ci dà la giovinezza eterna.

Cerca gioia e amore nella vita. L’amore è il rifiuto dell’odio e ci dà la giovinezza eterna.

Seek joy and love in life. Love is the rejection

of hatred and gives us eternal youth.

Ogni domani è importante per incontrare

nuova gente e vivere nuove e importante storie.

Every tomorrow is an important opportunity

to meet new people and live new and important stories.

And finally, never say you don’t have enough time. In a day, you have exactly the same number of hours that Leonardo had… and look at all the things he accomplished!

One Comment