A brief discussion and history of Francesca Goya

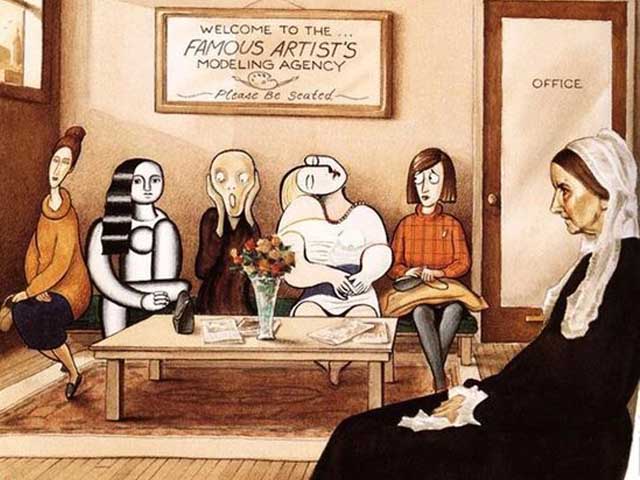

Celebrating the serious and the humorous aspects of great art

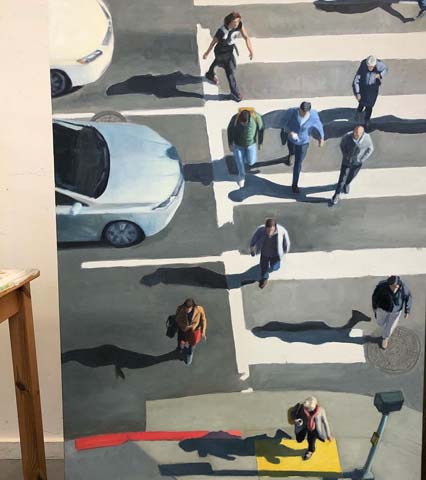

After seeing this meme on the internet today, I’m inspired to talk about Francesco Goya and two paintings he created called “La Maja Clothed” and “La Maja Nude.” All kidding aside, (apologies to the Spanish Queen Maria Louisa pictured above, painted also by Goya) the Maja paintings are among Goya’s most famous works of art in an oeuvre that spans a lifetime, that is visually unique.

Francesco Goya, a Spanish artist of the late 18th and early 19th centuries

Goya was a Spanish painter born in Fuendetodos, a small village in Northern Spain, on March 30, 1746. He painted about the time of the American revolutionary war. His full name is: Francisco de Paula Jose Goya y Lucientes. Early on, Goya showed interest in art and received encouragement from his father to pursue a career as an artist. He was apprenticed to a local artist and learned how to paint and draw by copying the works of other artists and masters.

Goya’s early career

At seventeen, Goya went to Madrid, Spain’s capital, and studied at the Art Academy. But, he received abysmal grades from the art selection committee. Undiscouraged, he began to make living painting portraits of the leaders of Madrid’s high society. About this time, Goya married his former art teacher’s sister, and they were lived together for thirty-nine years until her death. Of their five children, their only son, Xavier, survived.

Goya early in his career achieved notoriety with his portraits and as a result was invited by Charles III, the King of Spain to become his court painter. Goya accepted the position and set about painting portraits of the royal family and many the dukes and duchesses that lived at court.

Why does the young woman in the painting above turn her face away?

In Francisco Goya’s painting Charles IV of Spain and His Family the woman on the left who is turning her face away from the viewer is believed to be a member of the royal family whose identity was not yet determined at the time the portrait was painted. Many art historians suggest that she represents the future bride of Ferdinand VII, the king’s son, whose marriage had not yet been arranged. By leaving her face indistinct or turned away, Goya accommodated the uncertainty of her identity while still including her in the composition.

This detail aligns with Goya’s tendency to depict his subjects with an unflinching realism, often subtly critiquing their vanity and power. The entire portrait, while formally a royal commission, is known for its unflattering, almost satirical portrayal of the Spanish monarchy, reflecting Goya’s nuanced and critical perspective on the court of Charles IV.

The Maja Paintings

“Maja Clothed”

“La Maja vestida” or “Maja Clothed” was painted between 1800 and 1805. The term “Maja” is a Spanish word that refers to the smartly dressed female commoners on Madrid’s streets. The fashions they wore were similar to today’s punk rockers. They were considered very faddish and outrageous. Main stream society wouldn’t dare to wear the same thing.

“Maja Nude”

There is also an exact duplicate of this painting, but the model has no clothes! Why? Because people were so outraged by the nude image that they demanded that Goya paint over his original painting, putting clothes on the girl. Goya, however, refused to destroy his original painting and created instead a duplicate painting, putting clothes on it instead.

Who is La Maja’s true identity?

The paintings of La Maja Desnuda and La Maja Vestida are widely believed to be portraits of the Duchess of Alba, a close friend and possible muse of Goya. However, neither Goya nor the Duchess ever publicly confirmed this, and even today, the true identity of the woman remains a subject of debate. If the famous duchess had indeed posed for these paintings—especially while dressed as a commoner, a maja—it would have been considered scandalous in her time, as it would have blurred the lines between noble status and the street culture of Madrid.

On a fascinating side note, more than a century after the Duchess’s death, an unusual attempt was made to settle the controversy. In 1945, her descendants, eager to disprove any lingering association between their ancestor and the painting, went so far as to exhume her body. The goal was to measure her skeletal remains and compare them to the proportions of the woman in Goya’s portraits. Some contemporary relatives argued that the maja in the painting appeared too small in stature to be their famous ancestor. However, the results of this macabre investigation were inconclusive, leaving the mystery unsolved. To this day, speculation continues about the true identity of the enigmatic woman who captivated Goya and art lovers alike.

What do you think of how the la Maja is posed in Goya’s paintings?

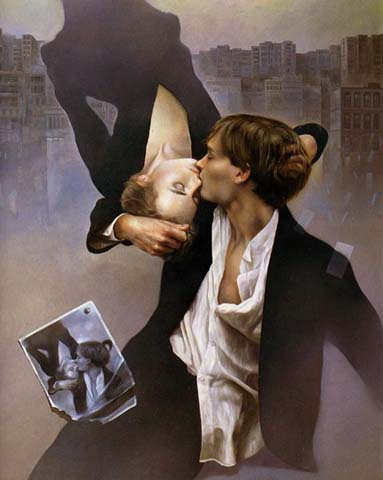

The subject reclines on a divan, her body fully extended and her gaze meeting the viewer directly. Unlike earlier depictions of reclining nudes, such as Titian’s Venus of Urbino, Goya’s Maja appears more assertive and self-aware, engaging the viewer with an almost knowing expression. Her hands rest naturally at her sides, yet there is an undeniable tension in the way she holds her head up, suggesting a certain alertness rather than complete relaxation.

If you were to be photographed or have your portrait painted, would you feel comfortable being posed this way? This question invites reflection on the vulnerability and confidence required for such a pose. Does the woman in Goya’s painting seem at ease, or is there a subtle discomfort in her posture? While her body is fully stretched out, her gaze and slight head lift indicate engagement rather than passivity.

This particular pose—showing a person reclining on a couch—is called an odalisque pose or a reclining pose. The word odalisque is of French origin and refers to a woman slave or chambermaid in a harem, though in Western art, it came to represent a stylized, exoticized depiction of a reclining female figure, often imbued with sensuality.

The reclining pose itself has ancient roots. Greek and Roman artists frequently used it to depict figures in funerary art, adorning tombs and sarcophagi with reliefs of reclining men and women, often symbolizing their transition to the afterlife. Over time, this pose evolved in European art, becoming a standard for portraying figures in both sacred and secular contexts, from religious imagery of reclining saints to Renaissance and Baroque depictions of mythological and allegorical figures. Goya’s Maja, however, strips away these traditional mythological justifications, presenting an unnamed woman in a direct and modern way, further challenging artistic conventions of the time.

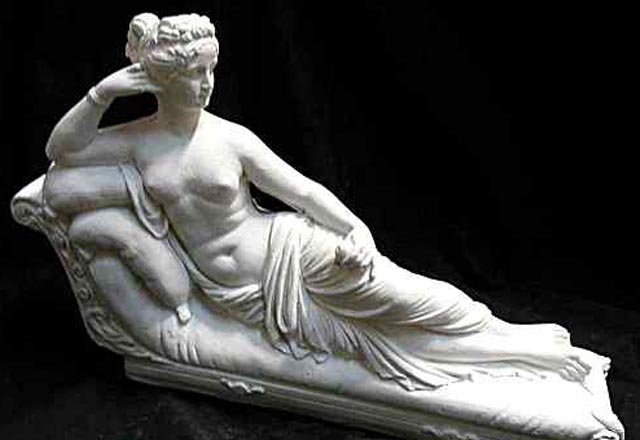

Portrait of Napolean’s sister Pauline by Canova

Here are examples of more contemporary portraits featuring the reclining pose. First, we have Antonio Canova’s neoclassical sculpture Pauline Bonaparte as Venus Victrix (1804–1808), in which he portrays Napoleon’s sister as a Roman goddess. This work exemplifies the continuation of the reclining figure in Western art, drawing inspiration from ancient Roman and Greek depictions of reclining deities and noblewomen. Canova idealizes Pauline’s form, sculpting her with smooth, marble-like perfection, yet he also imbues the work with a sense of sensuality and theatricality. By depicting her as Venus, the goddess of love and victory, Canova elevates Pauline’s status and aligns her with classical ideals of beauty and power, while also reflecting the aristocratic fascination with mythological imagery and self-aggrandizement. The sculpture thus bridges classical traditions with the more modern neoclassical aesthetic of the early 19th century.

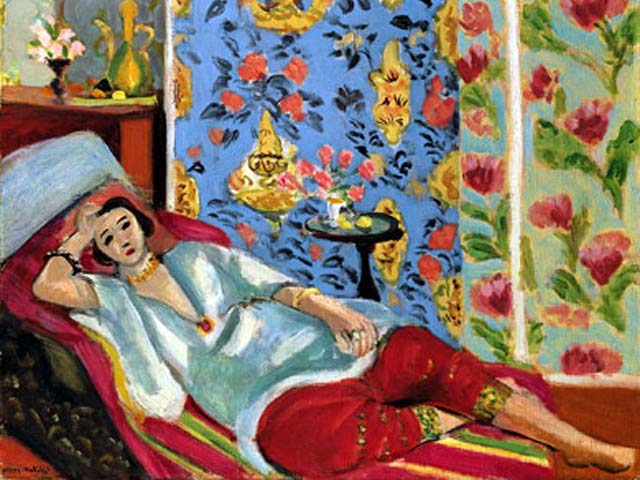

Matisse’s portrait of an “Odalisque in red pants.”

Matisse’s portrait Odalisque in Red Pants is another example of a contemporary portrait of a reclining figure that follows in the tradition of ancient Roman and Greek forms. In this work, Matisse reinterprets the classical reclining nude, a pose seen in ancient sculptures and frescoes, through his signature use of bold color, fluid lines, and decorative patterns. Rather than emphasizing anatomical realism, Matisse imbues the figure with a sense of languid elegance and exoticism, drawing on the long-standing European fascination with the odalisque motif. His approach modernizes the classical tradition, blending it with the aesthetics of Fauvism and an emphasis on color and composition over strict representation. Through this reinterpretation, Matisse connects the odalisque to both its historical roots and a more modern artistic sensibility.

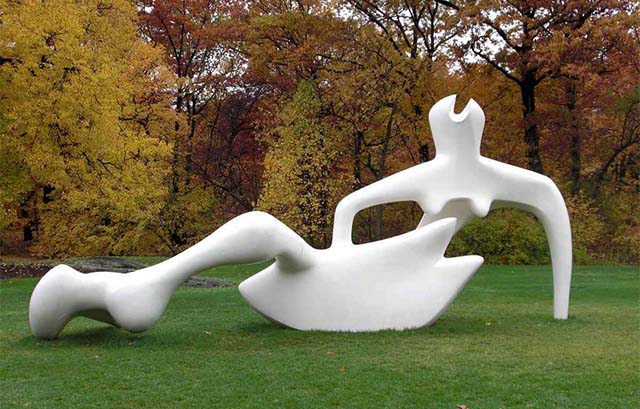

Henry Moore’s statue of a reclining figure.

And still, an even more contemporary example of the odalisque can be seen in Henry Moore’s statue of a reclining figure. Moore, a 20th-century British sculptor, reinterpreted the traditional odalisque pose by abstracting the human form into flowing, organic shapes. His reclining figures, often featuring elongated limbs and hollowed-out spaces, strip away the sensuality and narrative context of earlier odalisques, instead emphasizing form, volume, and the relationship between the body and the surrounding space. In doing so, Moore transforms the odalisque from an exoticized and passive subject into a powerful, modern exploration of human form and sculptural abstraction.

Goya’s Style of Painting and Use of Color

Goya’s painting technique is distinctly painterly, meaning he applied paint in visible, expressive brushstrokes, layering it to create texture and depth. Rather than simply depicting smooth, polished surfaces, he sought to capture the tactile qualities of materials, making objects feel tangible and lifelike. Take a close look at La Maja Vestida—how does her dress appear to you? Does it seem light and slippery like satin? Can you almost feel the texture of the lace on the pillows or the intricate embroidery on her jacket? Goya’s ability to evoke these sensory details adds to the realism and richness of his work.

Now, consider Goya’s use of color. Unlike the vibrant, luminous palettes of painters like Matisse, Goya’s colors tend to be dark, somber, and atmospheric. His figures often emerge from shadowy, almost murky backgrounds, creating a sense of mystery and depth. This dramatic contrast between light and darkness—known as chiaroscuro—heightens the emotional intensity of his paintings.

Some art historians speculate that the haunting quality of Goya’s later works reflects his own psychological struggles. In 1792, he suffered a severe illness that left him completely deaf. The persistent buzzing in his ears was so agonizing that it nearly drove him mad. From that point forward, he relied on sign language to communicate. It’s possible that his increasing isolation and deteriorating health influenced his artistic vision, leading him to embrace darker themes and a more expressive, almost dreamlike style.

Goya’s Subject Matter in his later years

Following his illness and the loss of his hearing, Goya felt increasingly isolated from the world around him. Cut off from conversation and social interactions, he turned inward, channeling his emotions and imagination into strange, haunting, and often nightmarish imagery. Rather than focusing on grand portraits, he preferred to sketch and draw rapidly, capturing fleeting thoughts and visions. Many of these drawings were later transformed into etchings on copper plates, a technique that allowed him to mass-produce his stark and expressive images.

In 1808, when war broke out between Spain and France, Goya was deeply affected by the horrors of the conflict. Witnessing the devastation inflicted upon his country and its people, he created Los Desastres de la Guerra (The Disasters of War), a harrowing series of etchings that depicted the brutality, suffering, and senseless violence of war. Unlike glorified battle scenes often commissioned by rulers, Goya’s prints were raw, unsparing, and deeply human, exposing the atrocities inflicted on both soldiers and civilians.

Even after the French were defeated, Goya remained disillusioned. He saw little hope in Spain’s political leadership, which he viewed as corrupt, lazy, and self-serving. This growing cynicism and personal despair found expression in his Black Paintings, a haunting series of works painted directly onto the walls of his home, the Quinta del Sordo (“House of the Deaf Man”). These paintings—filled with grotesque, nightmarish figures and dark, oppressive colors—reflect a mind tormented by fear, frustration, and disillusionment.

Despite his worsening depression, deafness, and the turmoil in Spain, Goya remained a respected artist. However, as his political views became increasingly critical of the monarchy, the Spanish king began to distrust him. Without royal protection, Goya feared for his safety and chose to leave Spain, seeking refuge in France. He lived out his final years in self-imposed exile, dying at the age of 81. Initially buried in France, his remains were later returned to Spain in 1919, and today, Goya rests in La Ermita de San Antonio de la Florida in Madrid, beneath a ceiling adorned with his own frescoes.

Goya Unveiled: A Glimpse into the Life and Art of a Tormented Genius

Goya’s La Maja Desnuda, along with his distinctive style and evolving subject matter, showcases his bold and unconventional approach to art. His painterly technique, use of dark and dramatic color schemes, and willingness to challenge societal norms set him apart from his contemporaries. From his early portraits of Spanish aristocracy to his later, more introspective and haunting works, Goya’s art reflects both the external turmoil of his time and his own internal struggles. His fearless depictions of war, corruption, and human suffering remain some of the most powerful commentaries on history and politics ever created. Despite personal hardships—including illness, deafness, and political exile—Goya continued to innovate, leaving behind a body of work that continues to captivate and inspire. Today, he is remembered not only as one of Spain’s most influential painters but also as a visionary who bridged the transition from the Old Masters to the modern era of art.