From Byzantine to Humanism: Cimabue Paved the Way for Giotto & Michelangelo

Cimabue: A Pioneer at the Crossroads of Art History

Cimabue (c. 1251–1302) was a Florentine painter who played a crucial role in the transition from medieval Byzantine art to the early Renaissance. His work marked a turning point in art history, moving away from the rigid, stylized figures of the Middle Ages toward a more naturalistic, human-centered approach that would later define the Italian Renaissance.

Before Cimabue, medieval paintings were characterized by flat, two-dimensional figures, elongated proportions, and gold backgrounds that evoked a divine, otherworldly realm rather than real human experiences. These artistic conventions were largely influenced by Byzantine art, which prioritized spiritual representation over naturalism. Perspective, depth, and lifelike proportions were of little concern—what mattered was creating an ethereal, symbolic space reflecting the power and mystery of the divine.

But in Cimabue’s time, Florence was on the cusp of a new artistic age. Artists were beginning to observe the natural world more closely, leading to the development of light and shadow, greater realism, and a more humanistic approach to religious imagery. This shift was driven by a renewed interest in classical Greek and Roman art, as well as evolving cultural and philosophical ideas that placed greater emphasis on human experience.

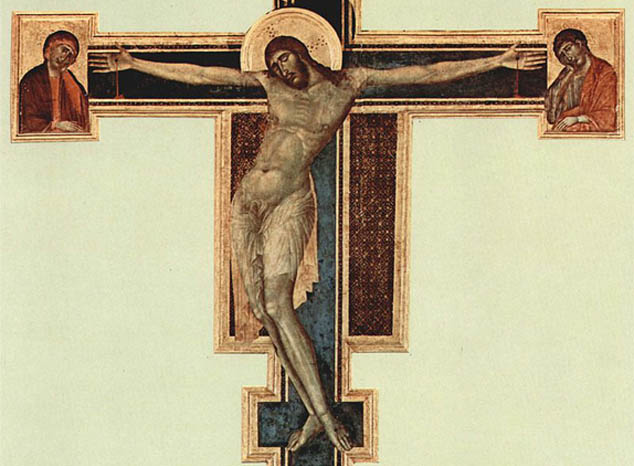

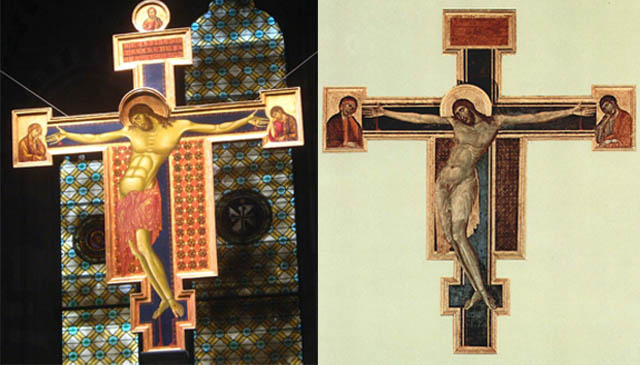

One of the first indications of this transformation can be seen in two crosses painted by Cimabue, one for San Domenico in Arezzo (c. 1240) and another for Santa Croce in Florence (c. 1268).

A Tale of Two Crosses: Comparing Cimabue’s Crucifixes in Arezzo & Florence

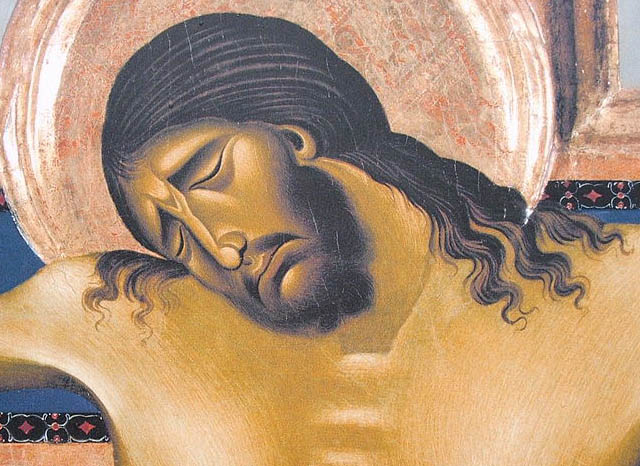

Both crosses feature Christ as the central figure, flanked by the Virgin Mary and John the Evangelist in small rectangular panels beside his outstretched arms. At first glance, traces of Byzantine influence remain evident, particularly in the gold backgrounds and overall composition. However, when comparing the two, we can see a clear evolution in Cimabue’s style, reflecting his growing departure from medieval conventions:

A Shift from the Triumphant to the Suffering Christ

Earlier medieval depictions of Christ on the cross often emphasized his divine triumph over death. But Cimabue introduces a more human and sorrowful Christ, marking an important philosophical shift. Instead of an otherworldly figure, Christ now shares in the suffering of humanity.

Increased Naturalism and Human Proportions

The Florentine crucifix shows a noticeable improvement in realistic proportions, moving away from the rigid, elongated forms of earlier medieval figures. Christ’s torso is more refined, his limbs are more fluid, and his S-curve posture is more pronounced, suggesting weight and movement.

Use of Light and Shadow (Chiaroscuro)

The Florence cross exhibits a more sophisticated use of shading, creating a sense of depth and volume. This would later become a defining technique in Renaissance art, perfected by Giotto, Michelangelo, and Caravaggio.

Breaking the Frame

In the Florentine version, Christ’s foot extends past the border of the cross, creating a sense that he exists within the viewer’s world rather than in a distant divine space. This technique anticipates the illusionistic realism that would later dominate Renaissance art.

The Survival & Restoration of Cimabue’s Santa Croce Crucifix in Florence

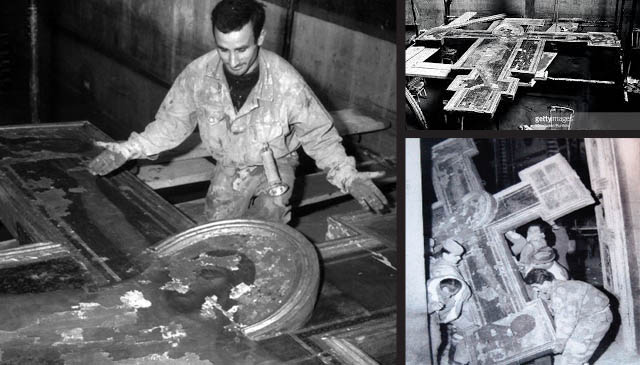

While the Arezzo crucifix remains well-preserved, the Florentine version has endured centuries of hardship. Over the years, it suffered damage from multiple floods, including: 1333 – The first recorded flood affecting Santa Croce, 1557 – Another flood causes additional damage, and 1966 – The most devastating flood in Florence’s history.

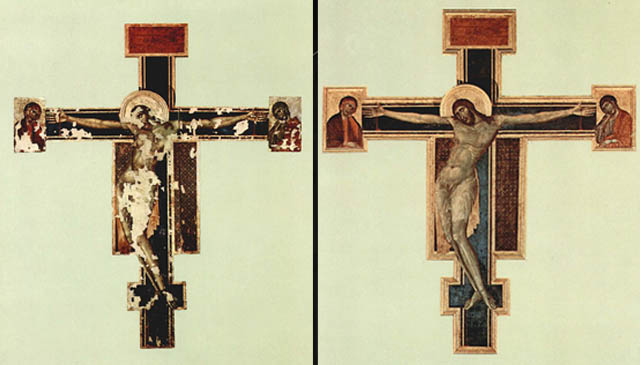

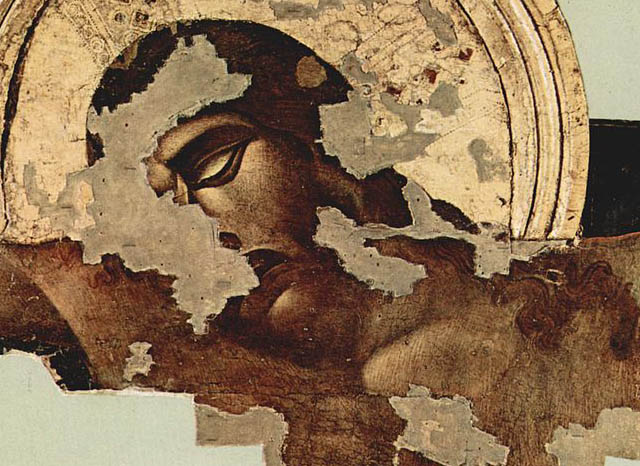

During the 1966 flood, the Arno River overflowed, submerging the Santa Croce Crucifix in muddy, oil-slicked water. The waterline inside the church reached Christ’s halo, causing the wooden panel to swell and cracks to form across the surface. By the time the waters receded, 60% of the paint had been lost, making it one of the worst artistic casualties of the disaster.

Restoring a Masterpiece

Led by art historian Umberto Baldini, a team of restorers spent ten years painstakingly reapplying paint that had been recovered from the floodwaters. To prevent further damage, they also separated the original canvas and gesso from the wooden backing, stabilizing the piece for future preservation.

By 1976, after a decade of careful restoration, Cimabue’s crucifix was returned to public display, though some of the damage remains visible today as a testament to its turbulent history.

Cimabue’s Lasting Legacy

Looking closely at Cimabue’s two Crucifixes, we see more than just religious imagery—we see an artist in transition, stepping away from medieval conventions and leading the charge toward the Renaissance. His work reflects a pivotal moment in art history, where artists began to focus on the human experience, ultimately shaping the trajectory of Western art.

But beyond the artistic transformation, Cimabue’s crosses also tell a story of resilience. The Florence crucifix, having survived centuries of floods, damage, and restoration, stands as a symbol of art’s enduring power and cultural significance.

Today, Cimabue’s influence lives on—not only in the masterpieces of Giotto, Michelangelo, and Caravaggio but also in the timeless quest of artists to bring depth, humanity, and emotion to their work. Watch the video comparing Cimabue’s work to that of his student — Giotto.