The Resurrection depicted by Italian Masters

The Art of Resurrection

Easter in Italy transcends religious tradition—it is a time of spiritual renewal, artistic awakening, and profound storytelling through paint, marble, and light. The Resurrection of Christ, as the cornerstone of Christian faith, has inspired some of the greatest artistic achievements in history. Across the centuries, Italian and Italian-influenced masters have returned to this sacred subject, each bringing unique vision, style, and emotion. From the Gothic elegance of Duccio di Buoninsegna to the heroic classicism of Michelangelo, this journey through Resurrection art offers a window into evolving spiritual sensibilities and the enduring power of divine triumph over death.

Gothic through Renaissance — Visions of the Resurrection

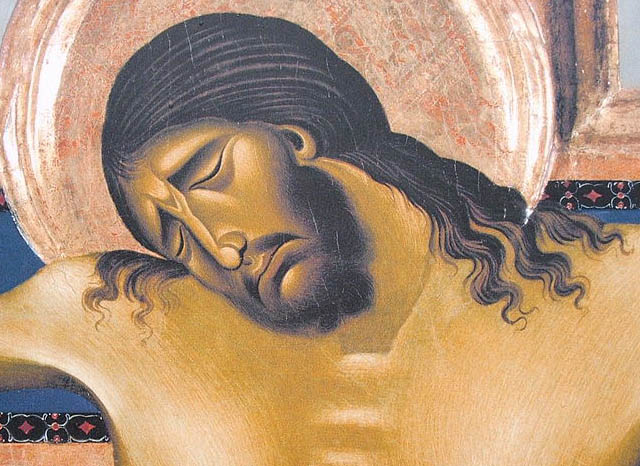

Duccio di Buoninsegna – The Appearance of Christ to the Disciples (c. 1308–1311)

Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, Siena | Tempera on wood, part of the Maestà Altarpiece

In the early 14th century, Duccio di Buoninsegna—founder of the Sienese school—crafted a luminous and tender vision of the risen Christ. In The Appearance of Christ to the Disciples, one of the many narrative panels within his monumental Maestà Altarpiece, we witness a moment of quiet revelation rather than high drama. Christ appears to His followers, calm and composed, radiating divine peace in contrast to the disciples’ astonishment. Duccio’s delicate brushwork, shimmering gold leaf, and refined Gothic lines evoke a world where the sacred is woven seamlessly into the everyday.

Duccio’s mastery lies in his ability to gently humanize the divine. Through subtle gestures and expressive gazes, he introduces emotional depth into religious art—a revolutionary step forward for the time. This panel stands as a precious link between the mystical iconography of Byzantine tradition and the emotionally charged storytelling that would soon define the Renaissance.

Giotto di Bondone – Noli Me Tangere (c. 1304–1306)

Scrovegni (Arena) Chapel, Padua | Fresco

Just a few years later, in the famed Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, Giotto di Bondone took another bold step in redefining sacred art. In his fresco Noli Me Tangere, he focuses on the intimate moment after the Resurrection when Mary Magdalene, overwhelmed by joy and disbelief, reaches for the risen Christ in the garden. Christ, in turn, gently halts her with a raised hand—“Do not touch me,” He says, ushering in a new kind of spiritual relationship.

What Giotto captures here is not just a biblical episode, but the emotional tension of human longing and divine mystery. His figures possess a newfound weight and presence, their gestures imbued with clarity and intent. The background, though minimal, directs all attention to this sacred encounter, allowing viewers to meditate on the threshold between earthly sorrow and divine revelation.

Giotto’s frescoes mark the beginning of a new artistic era—one grounded in human emotion, narrative clarity, and psychological realism. His work paves the way for the Renaissance, setting the stage for artists like Piero della Francesca and Raphael to explore the Resurrection with even greater depth and complexity.

Andrea Mantegna – The Resurrection (c. 1457–1459)

San Zeno Altarpiece, Basilica di San Zeno, Verona | Tempera on panel

Andrea Mantegna brought the Resurrection to life with sculptural clarity and classical drama in his San Zeno Altarpiece. In this striking panel, Christ rises from the tomb with commanding presence—tall, statuesque, and imbued with divine authority. His right hand is raised in benediction, while His gaze looks out across the ages, elevated against a sky painted with the first light of dawn.

Below, Roman guards twist in startled disarray, their bodies contorted in fear and awe. Mantegna’s mastery of perspective, anatomical detail, and architectural precision is on full display. He fuses Renaissance humanism with antique grandeur, presenting Christ not only as a risen Savior, but as a victorious figure of cosmic significance. The effect is one of monumental stillness—both theatrical and timeless.

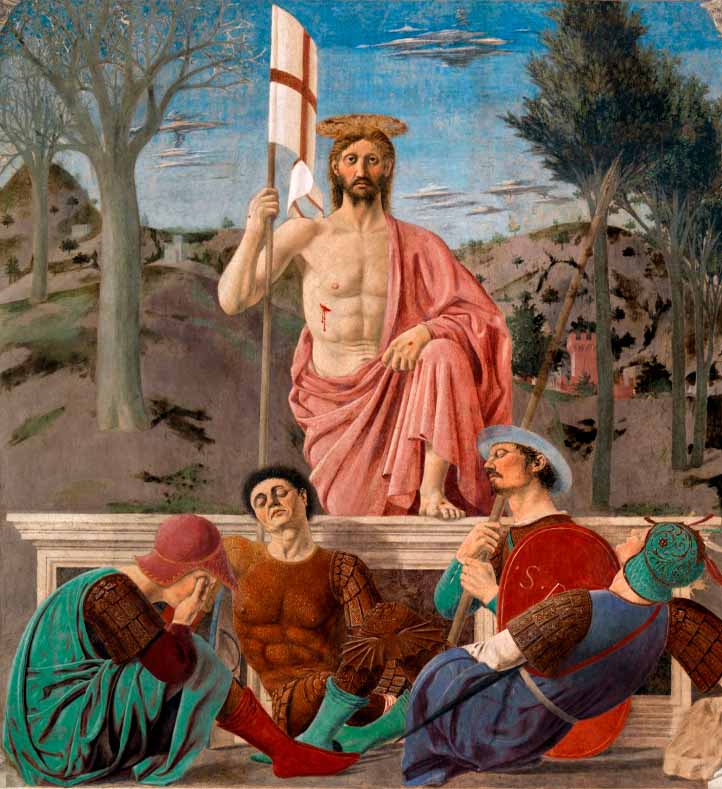

Piero della Francesca – The Resurrection (c. 1460)

Museo Civico, Sansepolcro, Tuscany | Fresco

In his hometown of Sansepolcro, Piero della Francesca painted what many have called one of the greatest masterpieces of all time—The Resurrection. Christ, wrapped in a rose-colored cloak, rises solemnly from the tomb with a gaze that is both serene and piercing. His calm expression seems to halt time, radiating a quiet authority as the dawn of redemption breaks behind him.

Beneath the risen Christ lie four sleeping soldiers, their bodies slumped in contrast to His upright form. The scene is symbolic as well as visually balanced: on one side of the background, bare winter trees represent the old world, while on the other, spring has begun to bloom—subtle testimony to spiritual renewal.

Piero, a master of mathematics and perspective, brought intellectual rigor and compositional clarity to this sacred subject. But beyond its geometry lies profound emotion. It’s no surprise that during World War II, the British officer in command of shelling Sansepolcro called off the attack to save this very fresco. It is not just art—it is a visual resurrection, one that brings stillness and awe to all who witness it.

Raphael – The Resurrection of Christ (c. 1502)

Museu de Arte de São Paulo (MASP), Brazil | Oil on panel

In his early twenties, Raphael turned to the Resurrection theme with a tender and harmonious brush. In this luminous painting, Christ floats above the tomb, radiating divine light, His arms open wide in a gesture of peace and transcendence. The composition is gentle, almost lyrical—closer to a celestial vision than a dramatic spectacle.

The guards below lie scattered in postures of astonishment, while angels hover in the background like silent witnesses. Christ, bathed in a soft golden glow, becomes the visual and spiritual anchor of the scene. Here, resurrection is not so much a moment of shock, but of sublime grace.

Influenced by his teacher Perugino and the Umbrian school, Raphael’s early Resurrection already reveals his genius for balance, clarity, and emotion. It prefigures the elegance and spiritual refinement that would define his later masterpieces in Rome.

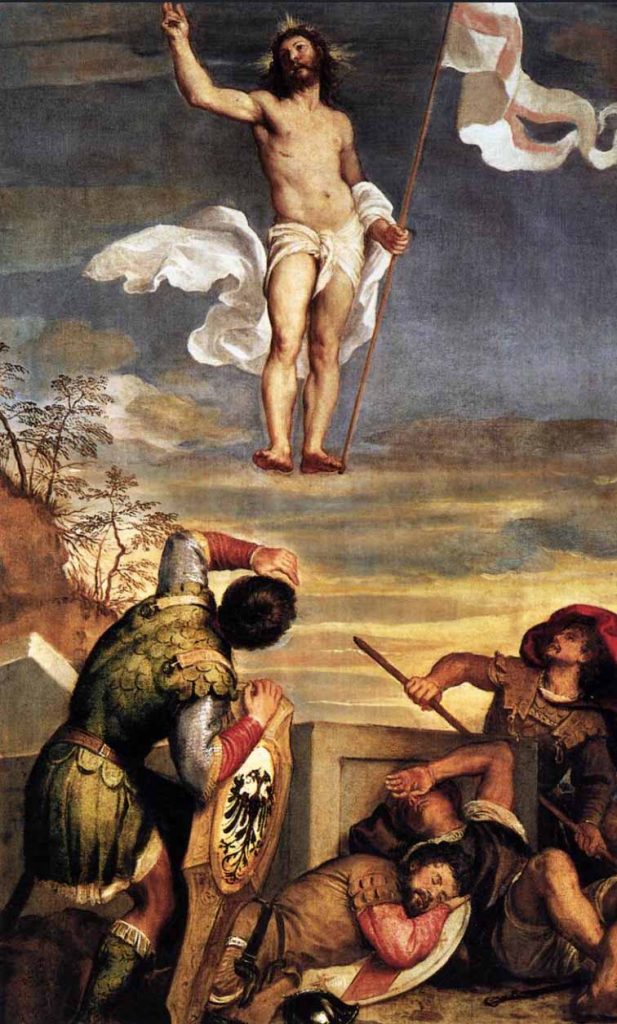

Titian – The Resurrection of Christ (c. 1520)

Church of Santi Nazzaro e Celso, Brescia | Oil on panel

With a bold flourish of color and movement, Titian brings explosive energy to the Resurrection. In this luminous altarpiece, Christ bursts from the tomb in a blaze of divine light, suspended mid-air, as if propelled by sheer spiritual force. His crimson banner of victory billows dramatically behind Him, cutting through the golden sky like a streak of salvation.

The soldiers below collapse in chaos and disbelief, shielding their eyes or tumbling backwards, overwhelmed by the supernatural event before them. Titian’s hallmark is on full display—his rich, sensuous palette, dynamic composition, and painterly textures breathe life into every inch of the canvas.

This Resurrection is not serene—it is triumphant, immediate, and all-consuming. Through brushstrokes and brilliance, Titian captures the visceral power of Christ’s rising, echoing the emotional intensity of Venice’s spiritual life and the grandeur of the High Renaissance.

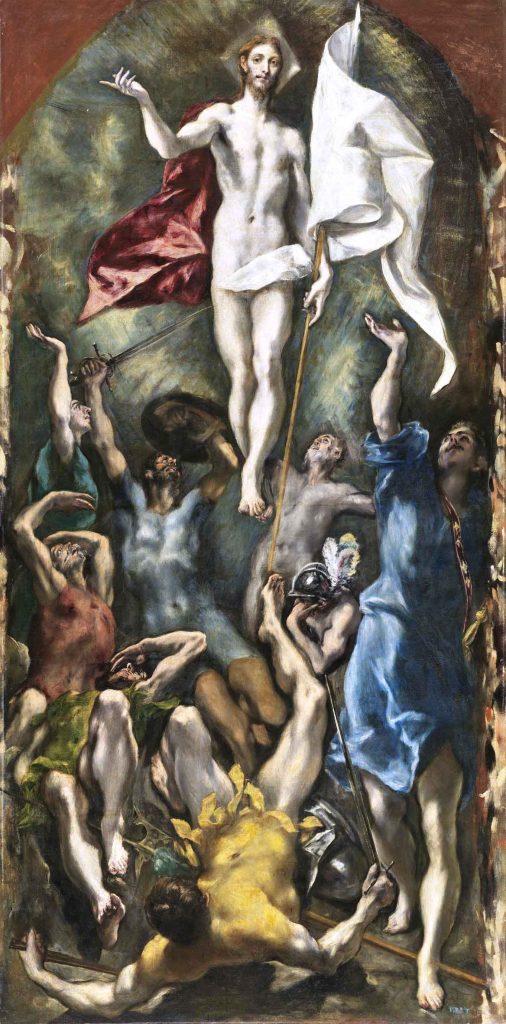

El Greco – The Resurrection (c. 1597–1604)

Museo del Prado, Madrid | Oil on canvas

By the end of the 16th century, the Resurrection takes on a new, transcendent form in the hands of El Greco. Though born in Crete and trained in Italy, El Greco’s singular style fuses Venetian color with Spanish mysticism and Mannerist elongation. In The Resurrection, Christ is a vertical beam of radiant energy—elongated, weightless, and aflame with divine light.

He hovers above the tomb, more spirit than flesh, surrounded by a swirl of movement and emotion. The soldiers below are cast in contorted fear, while the composition itself spirals upward, drawing the viewer’s gaze toward the heavens. Every line, shadow, and figure pulses with tension between earth and sky.

El Greco’s Christ does not merely rise—He ascends through light and color, transcending space and form. In this vision, the Resurrection becomes a mystical event beyond comprehension, one that stirs the soul more than the senses.

Michelangelo – The Risen Christ (1514–1521)

Santa Maria sopra Minerva, Rome | Marble sculpture

Unlike the narrative scenes painted by his contemporaries, Michelangelo’s interpretation of the Resurrection is a solitary, sculptural meditation. In The Risen Christ, also known as Christ the Redeemer, the master sculptor presents a standing, nude Christ—resurrected and radiant in classical perfection. His body is idealized, his posture open, his cross clutched with gentle authority.

There is no dramatic gesture or theatrical expression. Instead, the power of the piece lies in its stillness, in the way the marble seems to breathe and shimmer with quiet strength. Christ’s eyes meet ours not in judgment, but with profound serenity, inviting contemplation rather than spectacle.

Though the statue faced technical challenges—Michelangelo reworked it after discovering a flaw in the original marble—the final result remains deeply moving. It is a vision of the Resurrection not as a moment in time, but as a state of divine being, sculpted with reverence and awe.

Art as Resurrection, Resurrection as Art

Across centuries and artistic evolutions—from the golden stillness of Duccio’s Byzantine-influenced panels, with their flat, shimmering surfaces, to the harmonious realism of the Renaissance, the sculptural strength of the classical, and finally the ecstatic light and swirling energy of El Greco’s Mannerist vision—these portrayals of Christ’s Resurrection offer far more than historical testimony. They invite us into a profound and timeless dialogue between matter and spirit, doubt and faith, death and life. Every brushstroke, every carved fold of marble, every glint of pigment becomes an act of sacred witnessing—not merely to a moment in Christian history, but to the eternal human longing for transformation, renewal, and divine connection.

As we journey through the Easter season, we’re reminded that the Resurrection is not confined to ancient tombs or sacred altarpieces—it lives on in the courage to begin anew, in beauty rekindled, and in the hands of artists who dared to give form to the invisible. Through their vision, art becomes a window into the eternal, offering us not just something to look at, but a new way of seeing—a deeper understanding of what it means to rise, to hope, and to be transformed.

“Painting is a silent poetry, and poetry is a speaking painting.”

— Simonides of Ceos